For James Murray, editing the entry for khaki in the relevant section of the Oxford English Dictionary in 1901, the word was marked by its ‘exotic’ and non-naturalised status. Its form is, he states, ‘non-English’ while its initial consonant combination presented undeniable testimony of its colonial origins. As Murray further explained in the Preface to Volume V of the Dictionary:

In those pages of K which contain the non-English initial combinations Ka-, Kh-, Kl-, Ko-, Ku-, Ky-, these exotic words may be thought to superabound; yet it would have been easy to double their number, if every such word occurring in English books, or current in the English of colonies and dependencies, had been admitted; our constant effort has been to keep down, rather than to exaggerate, this part of ’the white man’s burden’.

Murray’s comments can, in this, serve to reveal still other facets of the on-going discourse of history and the history of words (even within the OED). Nevertheless, khaki — with its heritage in Urdū khākī ‘dusty’, f. khāk ‘dust’ — was one of the words which was admitted into the Dictionary without question, being further picked out, in Murray’s prefatory ‘Note’ to the fascicle Kaiser-Kyx, as an ‘interesting word of foreign origin’ –even if, like similar forms, it is judged an ‘alien’ or temporary ‘denizen’ in ‘our language’. In the Dictionary itself, the entry is prefaced by the ‘tramlines’ used throughout the first edition to mark out words where naturalisation is in doubt. Khaki variously appears in supporting evidence within the entry as khakee, Karkee, Kharkie, or khâkee . Use in English is traced back to 1857 and ends in 1900, a point by which, as Murray notes, khaki, originally used for British Indian recruits in the mid-19thC, was, as in the Second Boer War, ‘a fabric … now largely employed in the British army for field-uniforms’.

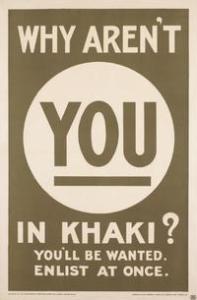

By the summer of 1915, the status of khaki in ‘our language’ was, however, open to some reassessment. As the Words in War-Time archive explores, its form had stabilised while its wide-ranging familiarization (across a range of meanings and registers) was undoubted. ‘Exotic’ in origin it might be but khaki had, by July 1915, become the prime image of active service, used in recruiting posters and campaigns, in advertising (for a surprising variety of products), as well as in news discourse and popular comment in ways which permeated Home Front as well as military use. Khaki can be noun, verb, and adjective, making its way into a diverse array of compound forms. It can, as this post will explore, also assume telling figurative and metaphorical uses, alongside its role in specifying quite literal aspects of the material culture of war.

Early uses in the archive confirm, for example, this material significance, as well as its location within entirely domestic contexts of production. ‘The khaki on order in the great Yorkshire mills runs to a length of ten thousand miles’, as the Daily Express recorded on Friday 11 November 1914: ‘Abnormal orders for Army clothing are now in order of execution’. ‘The Khaki Boom’ likewise stands as an arresting headline in the Scotsman on Tuesday 1st December; as the article explains, ‘Khaki mills in Leeds, and the West Riding generally, are taxed to the utmost capacity’. Khaki here signifies the distinctive cloth required for the abundance of new recruits (many of whom – in another locution of the war — had to be clothed in ‘Kitchener blue’ until sufficient khaki had been produced). Those so attired, as another except in the archive confirms, are khakied – in what can be depicted as a visible signifier of war-readiness:

‘The miles of khakied boys I passed through to-day are stimulated by the inherited spirit of their father’s fathers’,

as one of Andrew Clark’s least favourite war correspondents – Edwin Cleary – noted in in the Daily Express in November 1914. ‘Oxford Under Arms. Khaki Displaces Gowns’, states a memorable clipping – complete with picture – taken from the Daily Express in April 1915. The traditional oppositions of ‘townsmen’ and ‘gownsmen’ is not longer valid. Instead

Everywhere at this historic seat of learning are men in khaki. A detachment is seen at drill in one of the quiet quadrangles of the colleges’.

In another memorable clipping, the Scotsman in January 1915 spends some considerable time discussing the virtues of the khaki kilt.

As in the charity campaigns for the ‘“Khaki” Prisoner of War Fund’ which also appear in the archive , khaki’s wider use as signifier of war, and its connotations, is also apparent at a relatively early stage. The prisoners in question are not necessarily clothed in khaki (or in blue); khaki here denotes not cloth but the metonymic patterns by which it can be used to suggest war in general terms, or anyone on active service. ‘Mars is the patron saint of this year’s Royal Academy, as might have been expected’, as an account in the Daily Express of the Royal Academy exhibition in May 1915 declared. The result was ‘A Khaki Academy’ – one replete with depictions of war in which khaki as cloth is by no means necessarily present. As the article continued:

Vital art must be in touch with life, with the thought and emotions of the time. When everybody thinks and talks war, it is only natural that the art of the hour should breathe war; and so pictures more or less directly connected with the titanic struggle of the nations abound at Burlington House.

Such extended patterns of use, as in the example below, can be conspicuous in recruiting campaigns in 1915:

‘Is your “Best Boy” wearing khaki? If not, don’t YOU THINK he should be? If he does not think that you and your country are worth fighting for – do you think he is WORTHY OF You?

Not to be wearing khaki is positioned as a form of stigma, in a visual symbol of a rather different kind. To wear khaki is placed in topical meanings of ‘to have enlisted’ (and placed, by implication, against the negative rhetoric of ‘shirkers’ and ‘slackers’ which remains prominent in popular discourse at this time). The fact that the pressure to join up is channelled through the woman addressee (who forms the interpellated ‘you’) is also worthy of note (best boy — a common colloquial form, if one still absent from the OED –was assiduously recorded in the archive). Wearing khaki is thereby made to take on additional moral connotations of value and worth in ways which also serve to question the legitimacy of the individual ‘best boy’ as a worthy recipient of the addressee’s love. Khaki becomes, in essence, a test case of valour, of willingness to fight, and, indeed, of honour.

Advertising could make innovative use of meanings of this kind. As Clark notes in the Words in War-Time archive, advertisements for gramophones produced by ‘His Master’s Voice’ deftly assimilated ‘the khaki-colours of the times’. ‘Are you one of the ARMY’, an advertisement form the Daily Express in March 1915 demanded (even if the advertisement subsequently collapses into bathos with the revelation that the ‘army’ in question is that of ‘music-lovers’, and the zeal and activity required are those of purchase). More telling are the meanings of endurance and resilience, and the absence of cowardice that khaki must, by definition, now involve as deployed in advertising for Lux soap in May 1915. As readers were informed:

KHAKI NEVER SHRINKS FROM DANGER ON THE BATTLEFIELD, AND KHAKI NEVER SHRINKS IN THE WASH WHEN LUX IN USED.

Here, the punning references yoke khaki as fabric (which does not shrink – I,e, become smaller) when washed with Lux, and khaki as a signifier of bravery and courage when on active service of a different kind. Shrinking here involves the sense of retreat and fear; to shrink from danger is to avoid conflict, to preserve self at the expense of the common good. Khaki assumes an emblematic significance – if the army is khaki-clad, this can, in figurative uses of this kind, unite internal and external qualities in the resolution required.

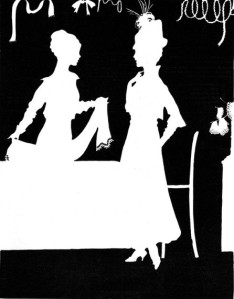

The figurative use of khaki has, as Murray’s original entry in the OED confirmed, a longer history. This was written, in fact, mid-way through another war. Khaki, Murray had noted, could emblemize ‘the war spirit in England at the time’, here with reference ‘to the South Africa war 1899—‘. The end of conflict remained unspecified. In Murray’s examples, ‘Khaki illusions’ (as in St. James’s Gazette in September 1900, ‘Khaki and Imperialistic allusions are worked in [to a play] to the entire satisfaction of the audience’) could signal a certain jingoistic zeal; khaki feeling an unwanted war-enthusiasm (‘Complications of all kinds are likely to arise as the khaki feeling dies down’). By 1914-15 such meanings had, however, shifted once more. Khaki’s figurative role is, at least at this point in WW1, made resonant of values which are both more positive, and less critical. As in the cartoon below, which appeared in the Sketch in 1915, a pithy exchange confirms the image of stalwart bravery and resolve which khaki can evoke. Khaki is steadfast as well as colourfast – neither it, nor its wearers, will not run in any sense of the word.

The Customer: “Will the colour run?”

The Customer: “Will the colour run?”

The Assistant: “Oh, no, Madam; it’s a khaki shade.”**

Notes.

For the OED and the language of empire, see Lynda Mugglestone, ‘Patriotism, Empire, and Cultural Prescriptivism: Images of Anglicity in the OED’ in The Languages of Nation. Attitudes and Norms edited by Carol Percy, Mary Catherine Davidson (2012).

; for the history of khaki as uniform in WW1, see Jane Tynan, British Army Uniform and the First World War: Men in Khaki (2013).

The cartoon in the Sketch is also discussed at http://www.illustratedfirstworldwar.com/2014/10/08/, where, however, the meanings are assumed to be literal rather than metaphorical.

One other worth noting is ‘Khaki Fever’ which was the alleged condition of young women and girls losing their moral judgement and decorum at the alluring sight of men in uniform. ( The alleged result of this might be ‘war babies’, see earlier entry)

On the moral language of uniforms, there is a cynical cartoon from 1916 which shows a civilian asking a man in Khaki uniform ‘Why aren’t you wearing Hospital Blue?’

LikeLike

On the look-out for khaki-fever in the archive … but nothing as yet in the summer of 1915 …

LikeLike

[…] meanings could, in themselves, swiftly seem démodé. With the coming of war, volunteers assumed khaki (or if khaki wasn’t available, Kitchener blue). Young men who did not volunteer were liable to be […]

LikeLike