Can we write a history of war through the words that are used ? If so, what might this reveal ?

In August 1914, Andrew Clark, rector of Great Leighs in Essex and a long-established volunteer on the (then on-going) first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, decided to document the impact of war on the English language. The 90 notebooks (and associated files) that he produced over the next four years, headed ‘English Words in War-Time’, provide a detailed and largely unexamined record of language on the Home Front, and the reporting of war in a critical period of social and historical change.

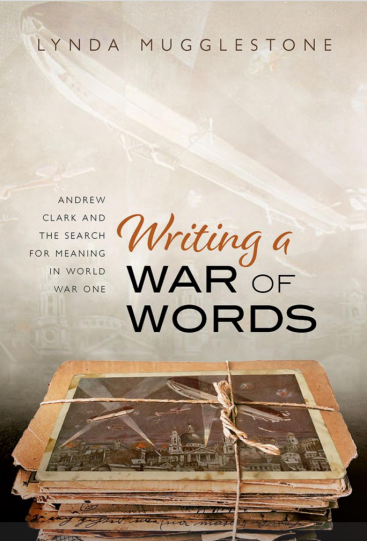

The ‘English Words in War-Time’ project initially tracked Clark’s emerging lexical history in ‘real time’ — if a hundred years later — in a series of blogs which will ran across the centenary of WWI. As these explored, 1914-19 was in no sense an era in which English either ran out of words (as Henry James argued) or in which innovation or expressivity failed. Instead, English was witness to a striking fertility and productivity, responding to the changes of material and ideological circumstance, to technological impetus and new constructions of gender identity and roles, as well as in terms of a changing language of memory and memorialisation. The book of the project Writing a War of Words. Andrew Clark and the Search for Meaning in WWI was published in October 2021 by Oxford University Press:

It featured on ‘Word of Mouth’ with Michael Rosen in January 2022: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m00139cm

The English Words in War-Time Project was supported by the John Fell Oxford University Press Research Fund and by the Leverhulme Trust.

With the centenary of the battle of Passchendaele, I undertook considerable research into the place and its environs before writing the poem ‘Passchendaele’. The poem ‘went viral’ within hours of publication, and demonstrates the fact that war poetry written today still strikes a chord with readers.

Passchendaele by Martin Ward

Passchendaele sits

on well-balanced soil

which is mainly sand.

Fertile land, the home

of market gardens once,

but underneath the surface

lies London clay.

When shells explode,

clay becomes the cap.

Sitting at seventy feet

above sea level, a ridge

that formed the highest place:

an important place strategically.

Not even a hill; the lip of a saucer

that cupped the spilled-over tea

and dragged them under.

No dregs here, but warm remnants

of dunked biscuits: Rich Tea;

Scottish Shortbread or Bara Brith.

Blood-red, brown-sludge lagoons,

clay-puddled by marching feet,

tracks of tanks or horses’ hooves.

The tight-lip has been removed:

flattened in a skeletal landscape.

A church stood on a mound,

but, unlike the flowers, sprung-up

again. It gained stain-glass eyes

that tell of teary Northern Towns,

of Southern Towns, of every town

that bled its youth into the soil around.

Like Canada geese and emigre Aussies

in film reverse returning like homing pigeons.

What is the definition of a mountain?

In metric, six hundred metres, or Imperial,

a summit above two thousand feet.

Passchendaele, or the third Battle of Ypre

was the result of a summit. This land laid bare

and flattened keeps exploding and soon

it will be a mountain, as another politician

calls for another war, or a farmer’s son

ploughs a shell left sown into the soil.

This quagmire has not clogged-up rifles

or stopped the tracks of tanks. Passchendaele:

a bloody battle in ‘The War To End All Wars’.

LikeLike