A souvenir, in the relevant fascicle of the Oxford English Dictionary, first published in January 1914, was defined as a ‘token of remembrance’ – one which usually, as it specified, took the form of ‘a small article of some value bestowed as a gift’ and, as such, constituted something ‘which reminds one of some person, place, or event’. Souvenir spoons are recorded in a citation from 1893, and souvenir cards in a citation from the Daily News in 1900. Notions of value were, however, in reality, able to be constructed in emotional as well as (or, indeed, often instead of) monetary terms, being based in the perceived significance of the event or occasion, or the circumstances with which the object in question was associated. Above all, the souvenir was defined by its role in commemoration, whether in private or public forms. It was a keepsake, the Dictionary explained – something kept for the sake of remembrance.

That war was, from the beginning, also made part of similar processes of commemoration and active recall is also clear. Some of this was, of course, deeply ironic, in ways which already took meaning and use in newly distinctive directions. Souvenir, a word identified as unassimilated and ‘alien’ in the OED (being prefaced by the distinctive ‘tram-lines’ or || by which non-naturalised forms were marked out), would, for instance, quickly acquire a set of subversive associations. ‘All shells are called “souvenirs”’, as a ‘Letter from the Front’, reprinted in The Star in November 1914, explained. Souvenirs of this kind came to embody an ironic form of gift-giving in which the enemy proved extraordinarily generous. That the Allies were, in turn, rendered wholly mindful of the Germans by such means was plain; as in the previous post, the image of Tommy, sheltering in his trench while shells of various kinds whizz overhead, is highly evocative. Gifts of this kind were best accepted from a distance – as well as reciprocated in kind. Were Tommy to be unlucky, such acts of remembrance were moreover inscribed in all too visceral ways. An article headed ‘Argument over a Bullet’, detailed in the Scotsman in March 1915, records in considerable detail the argument which ensued between two hospitalised soldiers over the same bullet – the “souvenir” in question — which had, in fact, passed through both of them.

Souvenir would, in such ways, participate in the kind of creative redeployment evident in so many other words for weapons at this time (see e.g. woolly bear, Jack Johnson, coal box). In the modern OED, this shift of sense is given as military slang (and, in contrast to the Words in War-Time archive provides, is dated only from 1915). Nevertheless, as the “argument” described above in the Scotsman indicates, shells –or bullets –as souvenirs could also be entirely material artefacts, personal possessions which acquire value because of the circumstances in which they are acquired. A further article in the Daily Express in June 1915, for instance, describes a ‘war-souvenir’ – a compound recorded in the OED only from the 1960s – and represented here by ‘the time-fuse of what the soldiers call a whiz bang’. Souvenirs of this kind are not gifts, but are instead opportunistically taken (here in a sense-division absent from OED1). War-souvenirs can, as the Words in War-Time archive confirms, assume sometimes surprising (and grotesque) forms by which’value’ can be mediated and constructed::

The Disappointed Turco. German’s Head as a War Souvenir.

Among the patients are a number of Turcos – a tough lot. One of these medieval sportsmen brought back a German’s head in his knapsack, and he was mad when they took it away from him. He considered it the most precious souvenir in the world, and they had to compensate him to keep him quiet (Daily Express, September 9th 1914)

This flux in meaning – souvenirs as given, souvenirs as taken – can, in terms of war, be made to participate in further manifestations of that ideological divide between ‘them’ and ‘us’. As in the diction of Louvaining (discussed in an earlier post), the language of plunder and piracy often informs British accounts of acquisition on the part of the enemy. The Germans, as readers of the Evening News were informed in November 1914, had been issued with plunder-permits. As the accompanying article reveals, these stand as further testimony to the moral degradation with which the Germans are prototypically imbued. Rather than souvenirs or artefacts which inform legitimate remembrance, the connotations are of theft and moral bankruptcy:

We are eagerly waiting another manifesto from the German “intellectuals” defending the comprehensive looting that has marked the German occupation of French and Belgian cities and villages. “Plunder-permits” are issued to the troops, we imagine, as rewards for good conduct, and privates, as well as officers, have filled their knapsacks with portable property in a manner that would have won the whole-hearted approval of Mr. Fagin.

Pillage-tickets presents a parallel form, documented in the Daily Express at the same time. Its propagandist intent is clear. Spoils acquired by the Belgians, for example, can attract a very different stance, moving back into the territory of legitimate gain, and the role of artefact as remembrance:

The Belgians … display the utmost dash and skill in this form of warfare, often going out several miles ahead of their own advanced troops, and seldom failing to return loaded with spoils in the shape of lancer caps, busbies, helmets, lances, rifles,, and other trophies … (Scotsman, 28th October 2014)

A similar stance is evident in an article in the Evening News on Thursday 25th March 1915. Hre, as we are told, ‘Other souvenirs are coming in, bits of a bursten shell, Prussian bayonets, iron crosses of the great 1915 crop’. The negative moral metalanguage is entirely absent, while this harvest of artefacts is depicted as part of a wider historical remembrance. War-souvenirs, as well as war- relics, are – by means of language – instituted as cultural forms (though the fact that the material value of the items is often slight is, of course, part of this differential positioning). Plunder-permits, by implication, sanction wide-ranging removal of property; war-souvenirs instead gain value as a form of private remembrance. ‘You should have seen all the stokers grubbing about after the action looking for bits of shell’, as a letter to the Evening News records in September 1914. Souveniring in a time of war can, as other reports make plain, also draw Home and active Fronts together. ‘Sacks as war-souvenirs’ were, for example, offered to the public in December 1914, here commemorating ‘Canada’s Gift’, and the sacks in which ‘the huge consignment of flour sent by the Dominions to the Mother Country was conveyed’. These were formally identified as ‘souvenirs of the war’ and, as readers were told, available at a price of five shillings with the proceeds being donated to the Belgian War Refugees Fund and the Prince’s National Relief Fund.

War-relics offers other aspects of what is presented as legitimate gain. ‘He had a number of war relics’, Clark writes in his War Diary, for example, in December 1914, describing the return of one soldier from the Front, together with the material objects he had gathered up while on active service. A war-relict in the form of a ten-inch shell – ‘otherwise known as the Ypres Express’ – is likewise documented in the Scotsman in December 1915. Displayed in Edinburgh, this apparently attracted considerable attention. ‘It is a formidable weapon’, the article announced, which ‘sounds exactly like an express train rushing through the air when heard from the trenches’.

Perhaps most surprising in the emerging discourse of souveniring and the forging of cultural memory is, however, that of war tours, and war tourists. The former are advertised in, for example, the spring of 1915, allowing visitors from the Home Front to engage in the varied delights of the ‘Khaki Tour’ (a weekend for 8 guineas), ‘The ‘Poincaré Tour’ (10 days for 19 guineas), or the ‘Tipperary Tour’ (variably priced) in the trenches at the Front. There was, of course, a caveat, in that tours are ‘subject to military contingencies’. Memory and the experiential nature of life at the Front are commoditized in advertising of this kind, while khaki (like Tipperary) further confirms the complex of associative meanings which such words have, by this point, firmly acquired.

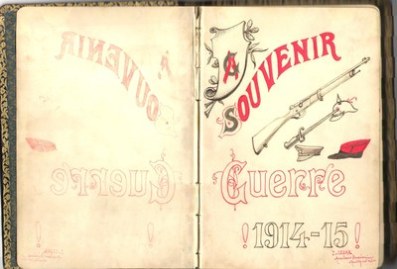

The Hennard album is interesting because souvenir is being used as the verb remember ( although it could also be translated commemorate or even ‘recall’) Souvenir de Guerre or Souvenir de la Guerre most often translates as war memoir.

The English use of souvenir in French would be ‘objet de souvenir’. What is interesting to me is that one might think the English word ‘keepsake’ might have served or indeed the established Latin import ‘memento’. (As well as the coinage war-relic). Speculatively- and this is your field more than mine Lynda, I wonder if they both had key draw backs. Keepsake suggested something that soldiers brought from home rather than acquired at the front. Memento might have suggested ‘memento mori’ which was possibly a bit near the knuckle.

Most tricky of all was the relationship between ‘souvenir’ and ‘loot’. Looting had been the standard practice of armies since time immemorial and probably the central motivation to combat. It had been more or less routinized before the middle of the C19th and it was simply accepted that enemy soldiers and all civilians would be robbed of their private property by the victors. Tightening international law and military discipline technically clamped down on looting in the 50 years before 1914 but practice in the field was more complicated. Taking an enemy soldiers helmet or pistol might be seen as ‘souveniring’ , an iron cross possibly, but what about a pocket watch or a ring? I think some soldiers recognised that something could be both a souvenir and loot and describing it as the former was perhaps an attempt to make it look respectable.

Souvenirs as inadvertent gifts from the enemy is an interesting thought. Conscious gift giving was of course central to the truces of the winter of 1914 (most famously Christmas) and what soldiers seemed to want above all was a tangible ‘souvenir’ of the event. But I wonder about ‘captured’ souvenirs whether they were at some level magical appropriation of the enemies power to harm ( as so often Blackadder 4 has provided an insight- Baldrick decides to own the ‘bullet with his name on it’ so it can’t hurt him).

War tourism is a whole other story and a fascinating one. We often forget how common this practice had been in past wars (Goethe at Valmy and an amazing number of civilians at Waterloo and American Civil War battles). In March 1915 Thomas Cook had to announce that they wouldn’t be conducting battlefield tours and requested that people not enquire.

LikeLike

Interesting to consider souvenirs as objects of commemoration and remembrance as they can often be seen just as ‘things’ (perhaps when the memory of what they are and what they signify has been lost?). The difference between souveniring and looting is also an interesting one which I hadn’t considered.

I notice that the term “war-relic” is mentioned here – is there any mention in the ‘Words in Wartime’ archive about the terms curio or antica/antika? I have found them used frequently for souvenir antiquities, particularly those from Egypt and wonder if their particular war-time meaning was ever catalogued?

LikeLike